“Who knows but that on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

-Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 581

Set primarily in 1948 tumultuous America, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is an evocative novel that deals with black identity, technological manipulation (Afrofuturism), social disillusionment, racial oppression, and invisibility. More broadly, the novel concerns individuality, tracing the numerous ways we sound our identities within political or communal networks. In the novel, an unnamed black man embarks on a Dantean journey from the South—where local white men mock him in the infamous “Battle Royal” scene and offer him a scholarship to a black college—to the basement streets of Harlem where the narrator finds a new brand of racism and where everyone he encounters, whether white or black, has an idea of who he is and what purpose he can play in their destiny. Invisible Man, which appears as one of the 100 Best English Novels (Time), is, as Lev Grossman wrote, “far more than a race novel, or even a bildungsroman. It’s the quintessential American picaresque of the 20th century.”

Although published in 1952, Invisible Man remains as pertinent as ever, particularly against the recent backdrop of race riots and social unrest in Ferguson and all too frequent incidents of racial profiling, often with dire consequences as in the cases of Oscar Grant III and Trayvon Martin; within a Canadian framework, the novel’s theme of invisibility heartbreakingly relates to the general invisibility of First Nations people, specifically the disappearance and murder of Indigenous women. Beyond its continued relevance, Invisible Man remains controversial for its honest depiction of racist America, as well as its voyeuristic sexual content, particularly the story of incestuous rape told by the signifying blues singer, Jim Trueblood. In fact, last year the Randolph County School Board voted to remove Ellison’s novel from its library shelves. Aside from the graphic content, abstract language, and historical scope of the novel, Invisible Man is also a difficult novel to teach because of its sheer size—a robust 581 pages.

Yet it is for all these historical reasons and challenges that I recently taught Invisible Man and will continue to do so. In a course structured around Sonic Afro-Modernity and Social Change we used the theme of sonic Afro-modernity (a term that comes from theorist Alexander G. Weheliye) to examine how Ellison’s interplay between sound technologies (the phonograph) and Black music and speech produced new modes of thinking and becoming, particularly allowing for new ways to engage with identity, temporality, and community.

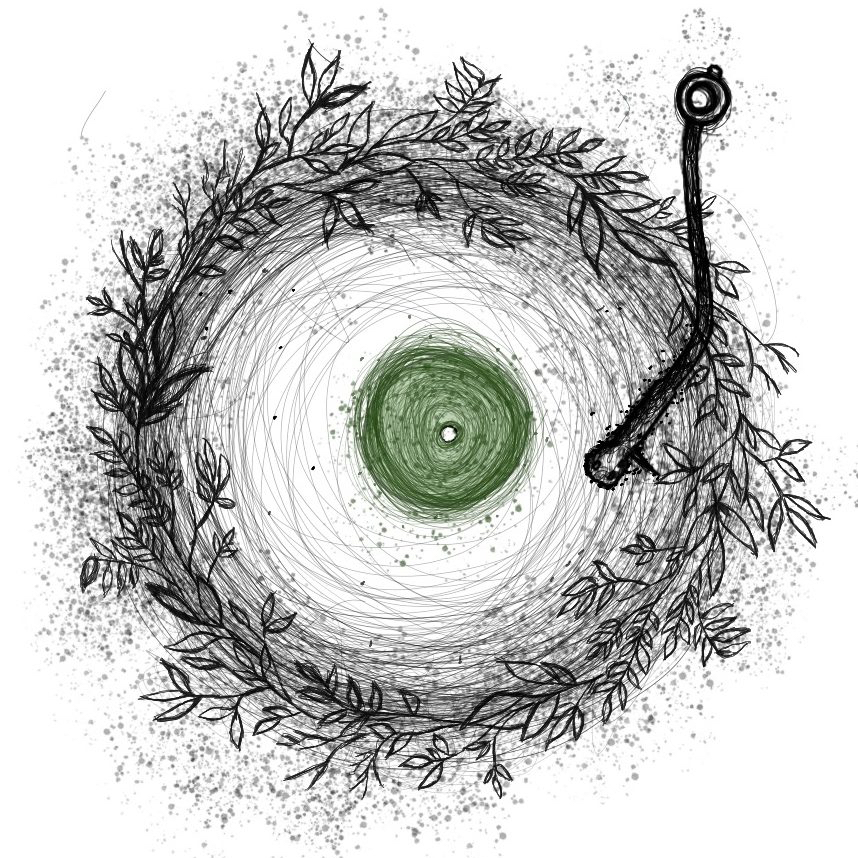

Ellison’s Invisible Man opens with the unnamed protagonist getting into the “grooves of history,” listening to Louis Armstrong’s “Black and Blue” on the phonograph—locating the music’s aura, as Wehelyie argues, “not in the original musical utterance but in the mode of mechanical reproduction itself, making him one of the foremost intellectual architects of sonic Afro-modernity” (47). Ellison’s unnamed narrator states: “Now I have one radio-phonograph; I plan to have five. There is a certain acoustical deadness in my hole, and when I have music I want to feel its vibration, not only with my ear but with my whole body. I’d like to hear five recordings of Louis Armstrong playing and singing ‘What Did I Do to Be so Black and Blue’—all at the same time” (7-8). Ellison’s choice to foreground Armstrong’s performance of “Black and Blue” (initially composed by Fats Waller) in the prologue to his circulatory text highlights how one articulates one’s historical somatic experience through the performance of identity.

The surreal hallucinatory episode of listening to the nodes of music via Armstrong’s own listening and discord of identity (with the aid of some reefer) becomes the act of improvised identity-performance for the narrator. The Invisible Man’s reimagining of the performance through a recorded performance—with a desire for simultaneous recordings—is the “authentic act” (in the non-authentic sense: that is, the performative nature of identity resists closure), where the grooves take the narrator inside and outside of history. Ellison—like a DJ mixing records to navigate a murky topology—creates a “mix” and becomes an innovator of “sonic Afro-modernity.” I use this example to show how there can be a politics at work in the DJ’s mixing (that “the mix” can articulate the layered nature of history, identity performance, and racial politics), and to emphasize that the DJ mix—certainly for Ellison—is an act of citizenship.

Through music I was able to index many of Ellison’s signifying strategies and show my students how identity—much like community and society itself—is a process that is always changing. As Ellison writes in his work Shadow and Act, “because jazz finds its very life in an endless improvisation upon traditional materials, the jazzman must lose his identity even as he finds it” (234), suggesting that Black identity, or any identity formed within improvising principles, is continually in process. Hence, jazz and, more ubiquitously, improvisation are about finding alternatives to dominant modes of being, which is why Ellison’s nightmare of living as a black man in America is also filled with possibility and hope.

There are moments when we realize (along with the narrator) that freedom can be as simple as walking down the street in our own skin proudly displaying our cultural heritage. For the narrator that comes in one moment (there are others) where he eats a cooked, syrupy yam on the streets of Harlem: “I walked along, munching the yam, just as suddenly overcome with a sense of freedom—simply because I was eating while walking on the street” (Invisible 263-64). No longer compelled to hide his Southern Black identity, the narrator ponders the connection between food and identity, feeling a profound sense of self-determination and autonomy—a sense that comes with progressing forward while simultaneously embracing, confronting, and remixing the past.

In this way, Ellison’s novel is prophetic (and Afrofuturistic): it speaks of change and resistance while acknowledging the cyclical nature and echo effect of oppression. History, as a metaphorical record, is distressed, scratched, and in need of a DJ (and an audience) to make it sound. Ellison, as a sonic architect, is an early progenitor of Afrofuturism: a movement that lets us know where we’ve been (from griot traditions and Egyptian pyramids and astronomy) to tell us we are going (mixing culture, technology, liberation, and imagination). As Afrofuturist Ytasha Womack writes of the movement, “It’s a way of bridging the future and the past and essentially helping to reimagine the experience of people of colour” (Guardian). Combating visions of tomorrow that view blackness as the failure of progress and technological cataclysm, Ellison shows that through the manipulation of technology, Black culture actually helped create modernity and notions of subjectivity, temporality, and community. History as remix, as a cyclical boomerang, allows Ellison to dig into the crates of the past to explore and expose the effects racism has on both victims and perpetrators.

Invisible Man deals with an entire “unrecorded history” (471) that is open for (re)interpretation and (re)examination, particularly by and for those groups of people who were once relegated to historical footnotes. We are thus challenged, as Robin D. G. Kelley argues in Race Rebels, to “not only redefine what is ‘political’ but question a lot of common ideas about what are ‘authentic’ movements and strategies of resistance” (4). Politics, as a “history from below” (5), also functions by what Kelley defines as “infrapolitics” (8), a term he uses to describe the circumspect struggle waged daily by subordinate groups who function beyond the visible spectrum. It is from “the lower frequencies” (581)—those subtonic bass notes—that the unnamed narrator (as a representative of the oppressed) continues to speak to a contemporary North America still recovering and living with the legacy and malaise of slavery, reformulated in some respects, under the guise of capitalism. Under this lens, we cannot trivialize contemporary acts of resistance by political youth movements like Occupy, Idle No More, or the Egyptian Revolution (2011, Tahrir Square), which effectively connected various people and global media outlets together to enact change—however grand or relative in scale and action. The recent First Nations Idle No More movement was the result of legislation (most directly Bill C-45) introduced by the Harper government, which violated treaty and land rights. Again and again: the record of history continues to spin.

Ellison’s Invisible Man remains a multifarious DJ mix of apposition and amalgamation. We encounter characters that personify actual historical figures like Booker T. Washington, Emerson, and Marcus Garvey and cultural references and influences that include Dante, Dostoevsky, T.S. Eliot, Melville, and Louis Armstrong. It is in this mixing, between Western classical and Negro Folk traditions (Shadow 190) that Ellison creates a polyphonic dialogue, displaying that Black music, literature, and culture are never fixed or stable, but rather layered and complex: the novel, like Brother Tarp’s chain, “signifies a heap” (388). Invisible Man matters because race and culture still matter. On a more global level, especially in the age of information and censorship, art still matters.

Reading (and making space to teach Invisible Man) remains an act of allowing one’s own identity position to be moved by the lower bass registers of sound. We are called to listen to those deemed to be on the lower registers of society. Ultimately, identity and, by extension, community involve the precarious act of yielding to others’ voices, which is at the crux of genuine multiculturalism and, often, interesting literature. I have an original first edition of the novel (3rd printing) and I can only imagine how people felt reading the novel for the first time in 1952. As I leaf through its taupe and textured pages, I realize that in spite of much change in terms of citizenship rights in North America, many of the power structures in the novel remain entrenched in our current society. When we finish the novel, a long endeavour, we (as the narrator does) are challenged to leave our holes of hibernation, “shake off the old skin and come up for breath […] even an invisible man has a socially responsible role to play” (581). The landscape might have slightly changed, certainly our understanding of the world via technology has, but our responsibility to make the world a better place remains as pertinent as ever. No wonder the highly visible want the book taken off the shelves.

Works Cited

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. New York: Vintage International Edition, 1995. Print.

—. Shadow and Act. New York: Random House, 1964. Print.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. New York: The Free Press, 1996. Print.

Weheliye, Alexander. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham: Duke UP, 2005. Print.

![RED REVISED Gustafson Poet Poster PRINT[3]](https://pauldbwatkins.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/red-revised-gustafson-poet-poster-print3.jpg?w=674&h=1024)

The artwork for the album is in itself a psychedelic trip.

The artwork for the album is in itself a psychedelic trip.